How did they know when to stop?

Why do we have periods in our Latin books then?

A teacher frequently encounters such questions in the teaching of Latin, especially during the levels I (beginner) and IV (advanced).2 Within the first year, questions will arise from native English speakers often regarding the word order of a Latin sentence, which in general will follow the flexible Subject–Object–Verb order.3 In this case, one may explain such a word order via the “lack” of modern punctuation, wherein verbs typically indicate a change from one sentence to the next. After this explanation, the student is usually satisfied and returns to their text, which is rich in modern punctuation.

Years later, upon working with authentic Latin texts, students will again ask questions similar to the ones they had in their first exposure to the language:

Did the original manuscripts have the same punctuation?

How do we know that this word belongs with this phrase and not that one?

These targeted questions arise when the teacher introduces the history of the text itself via Medieval manuscripts (if he or she does at all). Ultimately, readers of Latin, students and teachers alike, are at the whim of the editors, who determine and suggest how a line or a word should be interpreted. However, it is at this point that the investigative Latin student should realize that he or she is the ultimate interpreter, especially when it comes to punctuation, which can often be a hindrance in a text rather than an aid.

Through the lenses of beginning and advanced Latin classrooms, this note will discuss the role of punctuation in the Latin classroom, the history of Latin punctuation, and the benefits and detriments of the various systems of writing from ancient to modern. Before this, however, I would like to indulge in an anecdote involving some of my former students. In 2014 while student teaching in downtown Cincinnati, I had revealed to students that the Romans did not have punctuation as we have it now, if they had any at all depending on the time period. Naturally, they did not believe me at first, as 7th graders are prone to do, since their own books had Latin stories that were clearly marked in modern punctuation, from periods to lower–case letters.

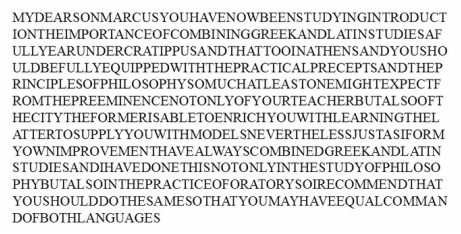

The next day, I brought in a variety of inscriptions and manuscripts, some with interpuncts, or word breaks, and others with no obvious punctuation at all, otherwise known as scriptio continua. “How could they read that, Mr. Wood?,” one student asked me. I will not lie; this is difficult for most Latin students to read, as they are not trained to read inscriptions, manuscripts, graffiti, or coins. In order to connect with my students more at this point, I decided to show them a sentence of Cicero, in English, but in scriptio continua:4

They understandably had difficulty reading this English translation from Cicero's De Officiis 1.1, until I added one small detail:

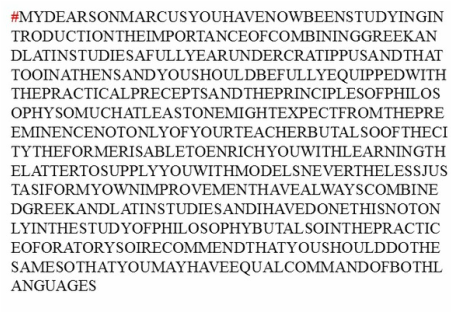

Once I added a hashtag (formerly known as the pound key for those of us who still remember land–lines) to the front of that periodic sentence, almost every student could read this because they had been trained to do so. It was second nature for them to read hashtags, especially obnoxiously long hashtag sentences on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, etc. Therefore, from my continuous experiments with this hypothesis, I argue that ancient media are not too difficult for today's Latin students; they simply need exposure reading the primary sources themselves.5

When introducing Latin to students, it is crucial to remember that the language was indeed a spoken language, in spite of the fact that we as educators will most likely emphasize the reading proficiency of Classical Latin: Caesar, Catullus, Cicero, etc. It would not be until the 7th century BCE that written Latin, such as the Praeneste Fibula, becomes a monumentalizing norm. In regards to this fibula, the text inscribed is rather difficult for students of Latin (and apparently for republican and imperial Romans as well), as it was written via Boustrophedon script, where words can be written backwards as lines of text, figuratively plowing across the writing field. Despite the initial difficulty, it seems worthwhile to me to introduce students to Latin at this point in time to give a full history of the written language and to lower anxieties that would arise when encountering interpunct and continuous scripts for the first time. Outside of the Etruscan–like Archaic Latin spelling and the Boustrophedon script, note the ‘punctuation’ used here: MANIOS:MED:FHEFHAKED:NVMASIOI.6

This colon–resembling double–interpunct is used to separate the words themselves. In the strictest sense, there is no punctuation used, as the double–interpunct does not denote clauses and sentences but only words. From this style, the interpunct apparently prevailed for centuries, all the way up to Hadrian's Pantheon inscription, as well as Septimius Severus' later inscription underneath the iconic letters.

Cicero himself calls these interpuncta verborum in his De Oratore 3.181, referring to the pauses of words.7

According to Elvis Otha Wingo, around 66 CE, a shift to an “interpunct–less” system came into common use, the scriptio continua, and by the 2nd century CE, this became the norm.8 The most noticeable characteristic is described in its name, that is “continuous writing”. Admittedly, scriptio continua is significantly more difficult to read in comparison to interpuncts. The best account of this is when the fourth century grammarian Servius critiqued Donatus for misreading Vergil’s Aeneid: interpreting Book II line 798 as collectam ex Ilio pubem instead of the actual collectam exilio pubem.9

This question of what words are which fall back to the very nature of Latin: it was a spoken language. Lengthy texts written down by scribes were meant to be read aloud, performed, or recited. As Paul Saenger notes in his Space Between Words, “Without spaces to use for guideposts, the ancient reader needed more than twice the normal quantity of fixations and saccades per line of printed text”.10 The very concept of silent reading did not exist.11 The “instances” of silent–reading from antiquity have been proven to be sub–vocalizations, a linguistic phenomenon similar to whispering or mouthing words, as proven by Saenger. From this tradition of avoiding embarrassment at first glance readings, we find manuscripts that are marked with a variety of “punctuation marks”: breaks, quotations, new paragraphs, etc.12 It seems that these scribe–annotated manuscripts became the basis for Medieval manuscripts, that then gave birth to modern punctuation, especially with the advent of the printing press.

It is clear that we as teachers have two general systems of punctuation to use when introducing students to Latin: modern or ancient. Let's begin with the modern. The most obvious advantage is that it uses the same punctuation as my our native tongues, whether they be Anglophone or otherwise European–based. This can remove the variable of legibility from our assessment of students with the language itself. Likewise, as I have stated earlier, the publishers' tradition has already been established. In combination with the touch of an editor, the question of how to interpret a text itself is entirely removed. While these are the advantages to modern punctuation, they are also the disadvantages to the ancient systems, from our modern perspective.

On the other hand, I will now outline the advantages of interpuncts or scriptio continua for today's students. First, I must acknowledge that when using these systems, especially scriptio continua, there is some ambiguity at times, but that is acceptable for a Latinist. In fact, I believe this is highly beneficial for the Latin student, whether a beginner or veteran. For novice students, they will immediately see the purpose of the Subject–Object–Verb word order, which Latin frequently employs. At the same time, they will also be introduced to the inner–workings of clauses, parentheticals, prepositional phrases, and the ever–tricky enclitics (–que and –ne) and postpositives (enim and autem).

For advanced students, they will be able to engage with the ancient texts directly, as poor Donatus attempted, and either serve as their own editors or engage with the editorial decisions made for them by someone else. This is a critical skill to develop for advanced readers: to investigate the primary evidence and to question the secondary sources when necessary. For example, a student should ask why a particular passage has an overabundance of semicolons. To quote a student of mine, “I’ve never used so many semicolons in my life”. Is that just the nature of the sentence, as in Cicero's De Officiis 1.1, or is there an editorial decision being made here?

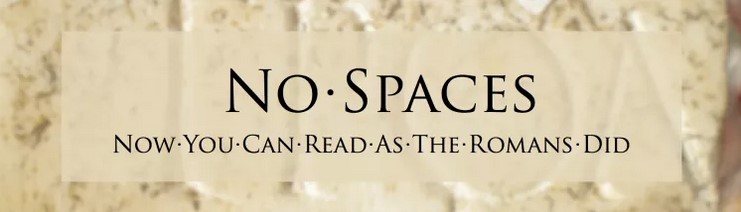

In addition, when using the Roman systems, we will be able to introduce students to authentic materials more quickly and more systematically. To put matters in perspective, students will be able to read an image of an inscription shown in class, not just dismiss it as just another picture in the textbook. In the same vein, by using the ‘Roman style’, we can transform regular lessons into thought–provoking activities — or to think of it in another way, when studying about Rome, read as the Romans did. Finally, my most regarded aspect of this system is that it encourages students to read Latin aloud. Whatever pronunciation of Latin you subscribe to, make them do it . . . often. Especially with this system, it is necessary and ultimately beneficial.

I can only advocate this so much; therefore, I believe that you need to try this for yourself either with your own personal studies or with your own students. To aid in this endeavor, I am happy to share with you a free resource, affectionately called NoSpaces (http://ionicempire.com/nospaces/).

NoSpaces is a web application that will convert any text you enter or ‘copy–paste’ into a variety of Roman scripts. I developed the app after mounted frustration from wanting to transform passages for class into the scripts described earlier. The traditional way to do this is to type a passage into a text–editor program, convert all letters to upper–case, find and remove all punctuation marks, replace all of the Us with Vs, and insert the interpunct symbol between each word. Any teacher who tries this method quickly realizes that this requires too much time for preparation and thus falls to the wayside. NoSpaces was coded to by–pass such efforts.

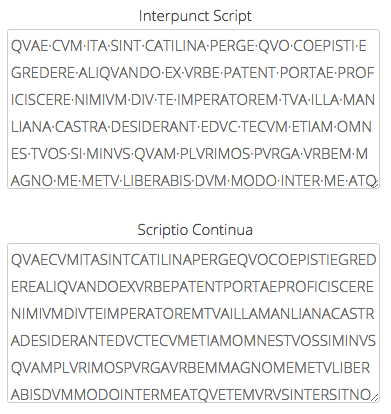

The most useful feature of the web app in my opinion is the various outputs it provides: with interpuncts, scriptio continua, and either one of those options but with the letter ‘U’ converted into ‘V’. From my experience using this with students, the ideal situation would be using scriptio continua with Vs; however, the option for interpuncts with Us is what I would recommend for most beginning students.

I will quickly outline how I introduced this to my current group of students.13 I first provided a quick overview of Latin (including Indo–European origins), beginning with the Praeneste Fibula inscription, followed by the Pantheon inscriptions to bring a more well known example to students. When it was time to actually read with a Latin passage, I used NoSpaces with scriptio continua with Vs to emphasize the Subject–Object–Verb order; after ‘intimidating’ them with the overwhelming nature of continuous script, we then used interpuncts with Vs to work through the passage. In addition to reading and translation exercises, I had my students first identify sentences from the punctuation–less passage. Reception was very positive, particularly when they read from the modern scripts for the passages. I can confirm that among my students there was a profound appreciation for punctuation!

The hope is that with the burden of creating your own texts removed from the equation, you will be inclined to give this a try in your own classrooms. I think you will find that your students will be enthusiastic about reading ‘real Latin’, and we will be another step closer to training and retaining more young Latinists in the classroom.

Bibliography

Hodgman, A.W. (1924). "Latin Equivalents of Punctuation Marks", The Classical Journal, Vol. 19, No. 7., pp. 403-417.

Knox, B. M. W. (1968). "Silent Reading in Antiquity", Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 9, pp. 421-435.

Parkes, M. B. (1993). Pause and effect: an Introduction to the History of Punctuation in the West. University of California Press.

Saenger, P. (2000). Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading. Stanford University Press.

Wingo, E. Otha. (1972). Latin punctuation in the classical age. Vol. 133. Walter de Gruyter.

- The original version of this paper was read at the CAMWS annual meeting held at the University of Colorado Boulder, in March 2015; I am grateful to Bartolo Natoli, for encouraging me submit this paper to CJF. Helpful remarks on the original paper were offered from fellow teachers and professors and have been incorporated as a result. To the students of Walnut Hills High School in Cincinnati, Ohio, I owe a special debt, without whom this paper would never have been conceived.

- See Hodgman (1924), 403: "The questions that students often ask about the punctuation in Latin texts show that they have not been told anything about the history of punctuation, or that the punctuation in any given text edition does not rest on any really ancient tradition".

- Cf. the rigid Subject-Verb-Object order in English.

- Translation by Walter Miller. On Duties. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1913.

- Similar arguments have been made in regards to Latin inscriptions and abbreviations around ten years ago with the birth of instant messaging (e.g. AOL Instant Messenger or AIM) and texting, but it is my observation that social media is a more centralized fixture of the culture of today's youth than AIM or even texting was a decade prior.

- The more Classical transliteration: MANIVS ME FECIT NVMERIO.

- Cicero: Hoc in omnibus item partibus orationis evenit, ut utilitatem ac prope necessitatem suavitas quaedam et lepos consequatur. Clausulas enim atque interpuncta verborum animae interclusio atque angustiae spiritus attulerunt; id inventum ita est suave ut, si cui sit infinitus spiritus datus, tamen eum perpetuare verba nolimus; id enim auribus nostris gratum est quod hominum lateribus non tolerabile solum sed etiam facile esse posset.

- Wingo (1972), 83-84.

- Parkes (1993), 10.

- Saenger (2000), 7.

- Cf. Knox (1968), 435.

- For a more in-depth discussion of these marks, see Parkes (1993).

- For Fall 2015, I am teaching Beginning Latin I for the University of Colorado Boulder.

Image 1: https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14785010123/in/photolist-7wvMKS-7wvMwm-owv3pD

Image 2: https://www.flickr.com/photos/isawnyu/7556337548/in/photolist-cvJcTS-bkt5Bg-5PDfhh-6AXXcr-juom4s-m98njp-5ZDt4m-jqa3mG-dZyi6o-kWPt9-jroLfS-jrmNNZ-mPsZqR-aTBY3x-wPodGA-aTBXDF-7enHUn-5YDhz6-8bixzg-5SHuV8-6179u1-bvXUYd-8V9oDj-bsH3bc-cgDr21-cB4j79-6WEWsr-a4x2BK-612WCc-pft2ma-9c9eTd-8G16wx-bh3fLt-3thn8-5avMS7-6BVuR9-9DczF1-3A3DFP-cdep9E-6joTp8-6joSft-aGjMTP-77oPd6-4DfmoX-9xiLWr-2Fk18-bikTU6-7X81yE-4dCyT8-2QP61h

RSS Feed

RSS Feed